First, a little background on the Real Stargate Project & the Ganzfeld Experiment. Then I’ll get into why I’ve created this site dedicated to ESP & Metal-ism Tricks.

The Stargate Project was a secret U.S. Army unit established in 1978 at Fort Meade, Maryland, by the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) and SRI International (a California contractor) to investigate the potential for psychic phenomena in military and domestic intelligence applications. The project, and its precursors and sister projects, originally went by various code names – ‘Gondola Wish’, ‘Stargate’, ‘Grill Flame’, ‘Center Lane’, ‘Project CF’, ‘Sun Streak’, ‘Scanate’ – until 1991 when they were consolidated and rechristened as the “Stargate Project”.

The Stargate Project’s work primarily involved remote viewing, the purported ability to psychically “see” events, sites, or information from a great distance. The project was overseen until 1987 by Lt. Frederick Holmes “Skip” Atwater, an aide and “psychic headhunter” to Maj. Gen. Albert Stubblebine, and later president of the Monroe Institute. The unit was small scale, comprising about 15 to 20 individuals, and was run out of “an old, leaky wooden barracks”.

The Stargate Project was terminated and declassified in 1995 after a CIA report concluded that it was never useful in any intelligence operation. Information provided by the program was vague and included irrelevant and erroneous data, and there were suspicions of inter-judge reliability. The program was featured in the 2004 book and 2009 film, both titled The Men Who Stare at Goats, although neither mentions it by name.

Background

Information in the United States on psychic research in some foreign countries was poorly detailed, based mostly on rumor or innuendo from second-hand or tertiary reporting, attributed to both reliable and unreliable disinformation sources from the Soviet Union.

The CIA and DIA decided they should investigate and know as much about it as possible. Various programs were approved yearly and re-funded accordingly. Reviews were made semi-annually at the Senate and House select committee level. Work results were reviewed, and remote viewing was attempted with the results being kept secret from the “viewer”. It was thought that if the viewer was shown they were incorrect it would damage the viewer’s confidence and skill. This was standard operating procedure throughout the years of military and domestic remote viewing programs. Feedback to the remote viewer of any kind was rare; it was kept classified and secret.

Remote viewing attempts to sense unknown information about places or events. Normally it is performed to detect current events, but during military and domestic intelligence applications viewers claimed to sense things in the future, experiencing precognition.

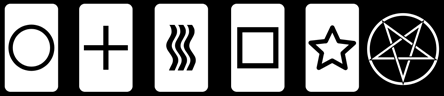

The Ganzfeld Experiment (from the German words for “entire” and “field”) is an assessment used by parapsychologists that they contend can test for extrasensory perception (ESP) or telepathy. In these experiments, a “sender” attempts to mentally transmit an image to a “receiver” who is in a state of sensory deprivation. The receiver is normally asked to choose between a limited number of options for what the transmission was supposed to be and parapsychologists who propose that such telepathy is possible argue that rates of success above the expectation from randomness are evidence for ESP. Consistent, independent replication of ganzfeld experiments has not been achieved, and, in spite of strenuous arguments by parapsychologists to the contrary, there is no validated evidence accepted by the wider scientific community for the existence of any para-psychological phenomena. Ongoing parapsychology research using ganzfeld experiments has been criticized by independent reviewers as having the hallmarks of pseudoscience.

Historical context

The ganzfeld effect was originally introduced into experimental psychology due to the experiments of the German psychologist Wolfgang Metzger (1899–1979) who demonstrated that subjects who were presented with a homogeneous visual field would experience perceptual distortions that could rise to the level of hallucinations. In the early 1970s, Charles Honorton at the Maimonides Medical Center was trying to follow in the footsteps of psychical researchers such as Joseph Banks Rhine who had coined the term “ESP” to elevate the discourse around paranormal claims. Honorton focused on what he thought was the connection between ESP and dreams and began exposing his research subjects to the same sort of sensory deprivation that is used in demonstrations of the ganzfeld effect, hypothesizing that it was under such conditions that “psi” (a catch-all term used in parapsychology to denote anomalous psychic abilities) might work. Honorton believed that by reducing the ordinary sensory input, “psi-conductive states” would be enhanced and “psi-mediated information” could be more effectively transmitted.

Since the first full experiment was published by Honorton and Sharon Harper in the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research in 1974, such “ganzfeld experiments” have remained a mainstay of para-psychological research.

Experimental procedure

In a typical ganzfeld experiment, a “receiver” is placed in a room relaxing in a comfortable chair with halved ping-pong balls over the eyes, having a red light shone on them. The receiver also wears a set of headphones through which white or pink noise (static) is played. The receiver is in this state of mild sensory deprivation for half an hour. During this time, a “sender” observes a randomly chosen target and tries to mentally send this information to the receiver. The receiver speaks out loud during the 30 minutes, describing what they can “see”. This is recorded by the experimenter (who is blind to the target) either by recording onto tape or by taking notes, and is used to help the receiver during the judging procedure.

In the judging procedure, the receiver is taken out of the Ganzfeld state and given a set of possible targets, from which they select one which most resembled the images they witnessed. Most commonly there are three decoys along with the target, giving an expected rate of 25%, by chance, over several dozens of trials.

Some parapsychologists who accept the existence of psi have proposed that certain personality traits can enhance ESP performance. Such parapsychologists have argued that certain characteristics in the participants could be selected for that would increase the scores of ganzfeld experiments. Such traits have included the following:

- Positive belief in psi; ESP

- Prior psi experiences

- Practicing a mental discipline such as meditation

- Creativity

- Artistic ability

- Emotional closeness with the sender

Critics have pointed out that relying on selection criteria like this can introduce bias in the experimental design, and so generally discussion of any claimed effects has typically included only studies that sample normal populations rather than selecting for “special” participants (see below).

Analysis of results

Early experiments

Between 1974 and 1982, 42 ganzfeld experiments were performed by parapsychologists. In 1982, Charles Honorton presented a paper at the annual convention of the Parapsychological Association that presented his summary of the results of the ganzfeld experiments up to that date. Honorton concluded that the results represented sufficient evidence to demonstrate the existence of psi. Ray Hyman, a psychologist and noted critic of parapsychology, disagreed. Hyman criticized the ganzfeld experiment papers for not describing optimal protocols, nor including the appropriate statistical analysis. He identified three significant flaws, namely, flaws in randomization for choice of target; flaws in randomization in judging procedure; and insufficient documentation. The two men later independently analyzed the same studies, and both presented meta-analyses of them in 1985.

Hyman discovered flaws in all of the 42 ganzfeld experiments, and, to assess each experiment, he devised a set of 12 categories of flaws. Six of these concerned statistical defects, the other six “covered procedural flaws such as inadequate randomization, inadequate security, possibilities of sensory leakage, and inadequate documentation.” Honorton himself had reported that only 36% of the studies used duplicate target sets of pictures to avoid handling cues. Over half of the studies failed to safeguard against sensory leakage and all of the studies contained at least one of the 12 flaws. After considerable back-and-forth over the relevance and importance of the flaws, Honorton came to agree with Hyman the 42 ganzfeld experiments he had included in his 1982 meta-analysis could not in themselves support the claim for the existence of psi.

In 1986, Hyman and Honorton published A Joint Communiqué which agreed on the methodological problems and on ways to fix them. They suggested a computer-automated control, where randomization and the other methodological problems identified were eliminated. Hyman and Honorton agreed that replication of the studies was necessary before final conclusions could be drawn. They also agreed that more stringent standards were necessary for ganzfeld experiments, and they jointly specified what those standards should be.